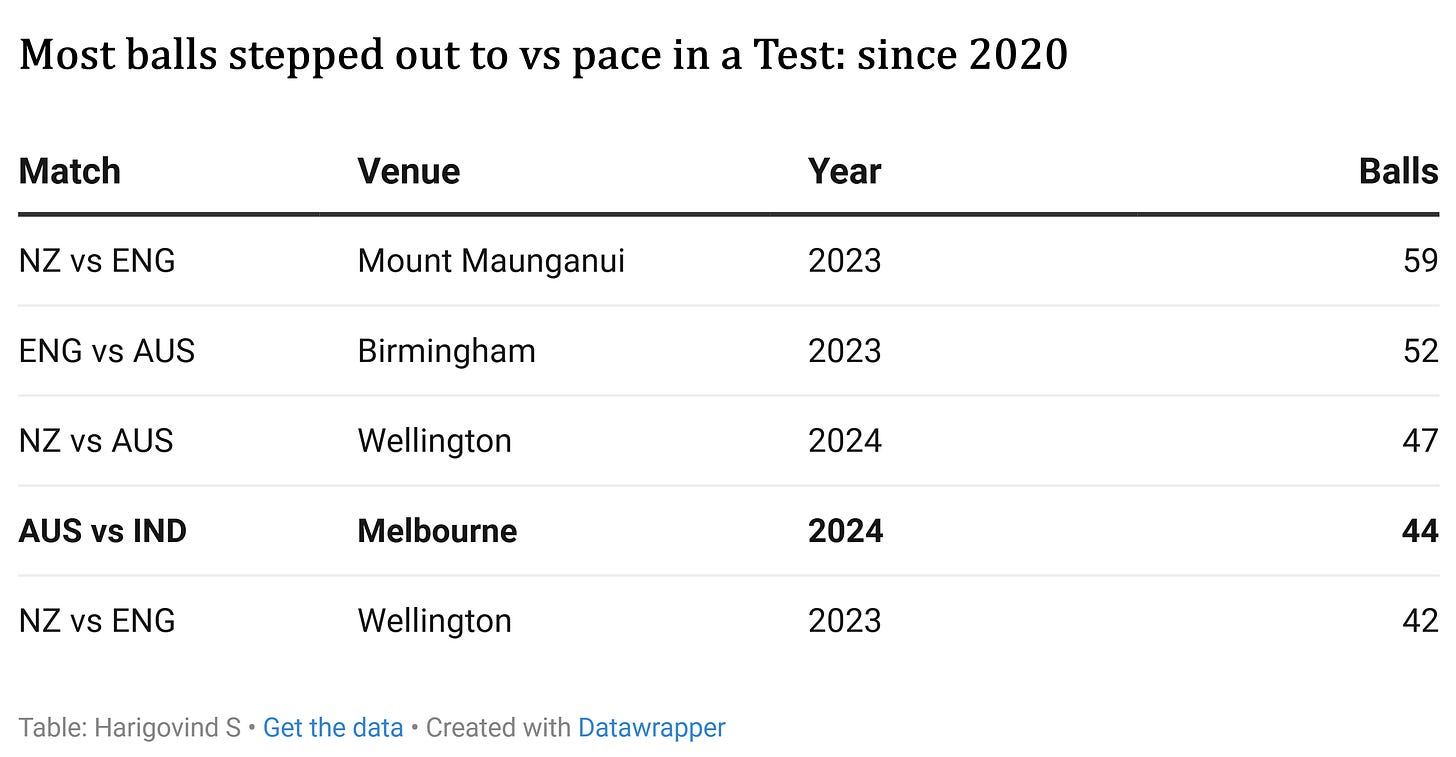

Three days into the MCG Test between Australia and India, we are already at the brink of a strange record. Batters from both sides have shimmied down the crease for a total of 44 times versus pace, already the third-highest among the 196 Test matches since 2020.

That’s not all. The Centurion Test between South Africa and Pakistan is not far behind, with just 18 other matches separating the two entries. Aside from being a statistical oddity, and the fact that the Melbourne Test is now likely to finish on the top of this list with two innings still to come, this is that extra bit interesting for a few different reasons.

Firstly, batters are not walking down the pitch with an attacking option in mind. In the top-placed match on this list, 7.42 runs flowed per over when batters came down the wicket against pace. At SuperSport Park and the MCG, though, the drive was offered only 38% of all the times batters came down the crease, and a defensive shot has been played half the times batters have stepped out. In all Tests since 2020, only 21% of such balls have been defended. If survival is your main interest when you charge down the track, why not simply bat outside the crease?

Except these players aren't exactly charging down the track. That's the second thing that makes this interesting. This is at best described as a timid step down the wicket. Not only are they not actively running down the pitch, they are also not advancing with their back leg shifting to the outer part of their leading leg to initiate the movement. What we have seen, on the other hand, is batters like Steven Smith and Yashasvi Jaiswal taking a short forward step in their trigger movements without their back leg crossing their front feet — a front-and-across trigger movement of sorts.

Lastly, the sheer number of players who have opted to do this is astonishing. In these two Boxing Day Tests, this list includes Smith, Jaiswal, Marnus Labuschagne, Usman Khawaja, Babar Azam, Saud Shakeel, Agha Salman and Tony de Zorzi. That's almost half of all the specialist batters in these games.

There have been popular explanations for why some batters have been doing the shimmy. For example, it has been suggested that Jaiswal has been walking down the pitch to negate Mitchell Starc's swing. But the observation that so many players have been up to the same thing suggests that this is at best an incomplete explanation; so does the fact that Jaiswal has used the same set-up in tandem to other bowlers. Here's what I think is going on.

In conditions where swing is the chief enemy of batters, it helps to bat outside the crease because this is a way to counter lateral movement. On the other hand, on a pitch with variable bounce, batting deep inside the crease gives you those extra fifty microseconds to make the adjustment should a ball bounce anomalously. Somewhere in the middle lies conditions with big seam movement: making contact far outside the crease helps by smothering the movement, but seam being something that can only be read off the pitch, it’s useful to have extra time to adjust.

In Australia and South Africa this year, the combination of these three batting nemeses has incentivized batters to mix their strategy: stay deep in the crease p% of the times and walk down the pitch (100 - p)% of the times. It also helps that the bounce in both these series, although inconsistent, has been high more often than low: walking down the crease on such a surface likely mitigates the dangers of lbw on an up-and-down pitch.

India have been at the receiving end of choosing to bat at the wrong end of the crease in recent years. The 2023 World Test Championship final, where Shubman Gill and Virat Kohli batted outside their crease on an inconsistently bouncing pitch, and the 2024 Perth Test where Kohli took stance a foot outside the wicket against big seam, come to mind. But elite cricketers are problem-solvers, and Pakistan and India both seem to have figured out a solution on tour in the bounciest conditions in the world.