Has T20 reached its dialectical conclusion?

Where to from here for the format?

In Phenomenology of Spirit, Hegel argued that the history of thought systems had reached its conclusion in 19th-century Europe. Through the process of dialectic, inferior thought systems had been replaced by superior thought systems, eventually resulting in the “Absolute Knowing” characterized by the epistemological processes which had been perfected in Hegel’s Europe. A few decades later, Karl Marx would extend this framework to the history of economic systems by suggesting that feudalism had been replaced by capitalism which would soon be replaced by socialism.

A similar argument is underway in cricket circles I frequent. It runs as follows. T20 in its early days suffered from being too closely tethered to the longer formats. Since players of this era were produced by systems which prioritized learning red-ball skills, they had a hard time internalizing the implications of having 10 resources to expend over 20 overs, such as the importance of fast scoring and slipping in the odd variation. But in recent years, driven by the exit of these players from the circuit, and a growing understanding of the financial prospect presented by the 20-over format, the system has changed its priorities in ways that you know as intimately as I do. These changes, it is argued, have resulted in T20 being “figured out”. In other words, the format has reached its Hegelian “End of History”.

The initial feeling I have about this case is suspicion, because the grander the thesis the more circumspect I like to be around it. Unpredictability is a key element of complex systems, and if the claim I put forth in a previous article is correct, then this is even more the case in sport. Perhaps climate change will make it impossible for future pitches to be as flat as they are right now, or maybe cricket’s most important nation will be the site of violent political upheaval and an authoritarian regime that champions the didactic qualities of the longer format will come to power. Moreover, it strikes me that the end of history as proclaimed by Hegel and Marx arrives at an extremely convenient time — when their architects are alive and well. So I am biased towards being optimistic about the future of the T20 format, not least because I really like it.

Now I know what the counterargument here will be. Of course there are going to be short-run fluctuations around this equilibrium, but if we zoom out into the long term, we will see that every five years or so T20 is going to spit out the same length splits and the same attacking shot percentages. Fair enough. Essentially you don’t think that the “improvements” that are remaining to be made in the format are individually substantial enough to take the format to a further level. Now this is a claim I feel more ambivalent about, so the best way to address it would be to list some of the ways in which I think the T20 format will undergo transformation in the coming years. And you can be the judge of whether they are substantial or not. What follows in the rest of this article is part argumentation, part prediction.

Trick shots

It is a pet peeve of mine that a reason why many viewers struggle to appreciate the aesthetic quality of T20 is that they track the wrong variables. While it pays when watching Test cricket to maintain a mental database of the lines and lengths being bowled, the best way of watching a batting-dominant sport may be to follow the batter’s moves. And this can be great fun because different batters use such different methods of generating force. Just consider Abhishek Sharma, who can make room to slash on the offside either by pre-emptively moving across, or pushing himself to the onside by pivoting on his front leg, or simply twisting his torso. T20 batting ought to be seen like it is boxing, where fighters bend their bodies into different shapes and forms to generate maximal force to impart to the ball.

What is the ultimate gimmick in boxing? A good feint. A feint is when a boxer pretends to go for a jab to the head but this is just a trick to get his opponent’s hands up so he can go to the body. In badminton, this deception takes the form of “trick shots”. This has been a facet of T20 hitting too — think of Jos Buttler pretending to change his handedness to nail a reverse sweep but then bailing out — but it is only recently that I have seen this general principle being employed in less set ways. Of the players I closely follow, Nitish Kumar Reddy has championed this the most, zipping to his left and zooming to his right while the bowler is running in but eventually returning to his neutral position. In a world where bowlers master the art of being vigilant to pre-release movements, trick shots could be an inevitable result.

Accessing the third dimension

If we were to conduct a serious analysis of the player-level causes for the run inflation in the IPL, increased movement around the crease by batters will feature somewhere near the top. It is now customary that on days when bowlers don’t give you the right line, you manufacture it by stepping around the crease (which may be thought of as translating your position along an imaginary x-axis). On the other hand, when it is the right length that eludes you, you can manufacture it by walking down the pitch or staying deep in the crease (which may be thought of as translating yourself along an imaginary y-axis). Now, the way I’ve framed this should signal to you that this list of maneuvers is inexhaustive, for there is a third dimension of space that remains largely unexplored.

A boxing parallel once again helps explicate this. A popular combination used by fighters is to duck while avoiding an incoming hook and follow it up an upper cut. Why is this combination lethal? Because the act of bounding back up helps impart force to the down-to-up motion characterizing an upper cut. Similarly, batters in cricket might use movement along the vertical dimension to make full deliveries shorter, like Rishabh Pant with his fall-down scoop, or short deliveries fuller, like Brendon McCullum used to do with his leaping cut shot. A related example is the helicopter shot as played by MS Dhoni. By crouching down before emerging, he would not only get his hands closer to the yorker but also use the ground as a springboard. In sum, accessing the third dimension could be T20’s solution to the hard- and yorker-lengths problem.

Variation and the bad bowler

This will cheer you up if the last two observations have had you throwing your arms up in disgust.

It is a known fact that players from countries lacking well-oiled systems tend to be more individualistic in character (the Indians could never have invented reverse swing or produced Lasith Malinga for this reason). This causes them to imbibe more of what we see as funky, and even though their basics are not the strongest, it makes them better short-format cricketers. Consider how happy the Netherlands batters are to play the reverse sweep or how diligently Oman’s Shakeel Ahmed darts it from a round-arm angle. The rising acceptance of variation will mean that the bad bowler of the 2030s won’t be as bad as the bad bowler of the 2010s.

Look around and you’ll notice that this is anything but an Associates-only phenomenon. Axar Patel now varies his speeds. Saim Ayub has perfected his inswinger. Nasum Ahmed and Riyan Parag bowl kick-ass round-arm deliveries. The importance of variety in the 20-over format will only rise as batters will look to hit every ball out of the park, since in order to do this they will need to commit to their motor choices much sooner in the hitting task. And variations are an easy skill to pick up for bowlers, at least a lot easier than it is to learn how to land everything in the proverbial handkerchief. So while a large part of good spin bowling will continue to be about imparting zip to the ball and landing it in the right areas, bowlers who cannot do this will teach themselves how to hold their own with the help of variation. In other words, the lowest quintile of twirlers could experience a resurgence.

Offside, behind square

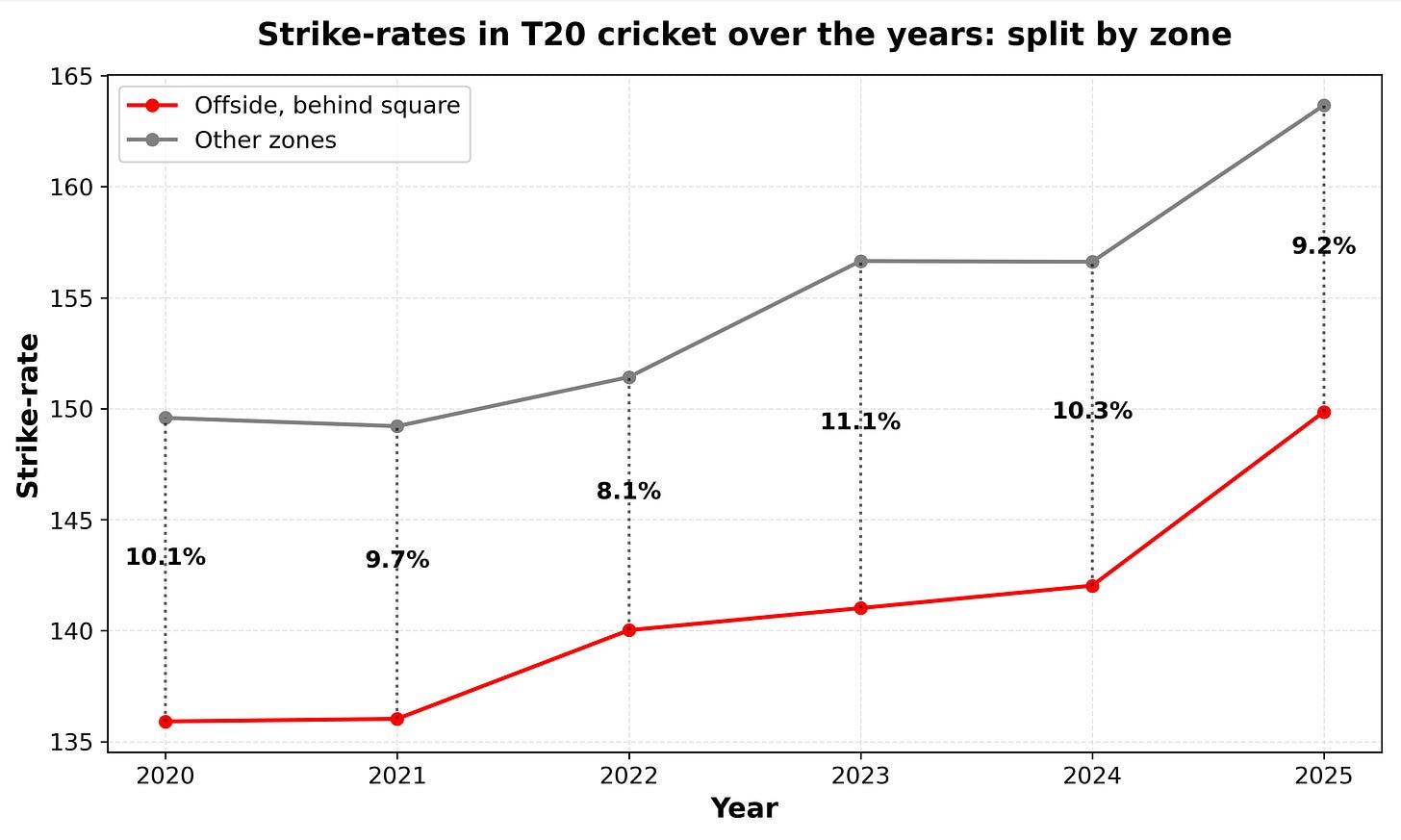

This is a more cautious suggestion, but I think that we are slowly seeing a new part of the cricket field being opened up. So far, it has seemed that the only way of accessing this zone of the field off good deliveries is by pre-emptively altering your handedness, by either playing the switch hit or the reverse sweep. But in Phil Salt and Travis Head, we have two mavericks who are proving it is possible to play the cut shot off even third-stump deliveries. How do they pull this off? By waiting on the ball long enough to put sufficient space between the ball and their hands to give it a whack. Then again, this seems like it could be a shot that requires superhuman wrists to carry out, so I’m not fully convinced it could be replicated by mortals. But expect me to shoot my hand up and say “I told you so” if the next generation of hitters are experts at cutting off their stumps.

The importance of bookkeeping

The biggest consequence of the hitting revolution is that it has made power-hitters absolutely enormous at vanilla power-hitting tasks. Slogging an overpitched ball over midwicket? Check. Depositing a long hop over the spinner’s head? Check. Going hammer and tongs against a wide one? Check. T20 has made the strengths of many hitters doubly strong while keeping their weaknesses equally weak. This makes it vital that bowlers move past strategy based on low-specificity-but-high-generalizability info and replace it with high-specificity-but-low-generalizability strategy. The friendlier the track and the fiercer the batting, the less conditions-oriented and the more player-oriented strategy ought to be. Information can surely be collected anecdotally, but as the saying goes the plural of “anecdote” is “data”. This makes me optimistic about the future of data nerds in the T20 circuit.

i think cricket is fundamentally a game of 'balance', &, like with any high-risks / high-reward strategy (i.e., t20's supposed modus operandi), when it comes down to the 'big moments', it is human instinct to go back to basics, do what you know, and play it safe.

thinking out loud but this is why the narratives around tests always appeal more to me: t20 tries too hard to be the cool rebel kid (even though when it truly comes down to it, it too goes back to relying on the basics). tests are unafraid to acknowledge that there is a place for both, and you switch gears as and when it's needed.

which also (ofc) ties back into all those thoughts around kohli's obsoleteness as a t20 batter in 'today's game': there will always be room for those kinds of players; & it will be unfortunate if t20's glaze blinds emerging players to that reality (— would be fun to see it in action @ sunday imo)

(sorry for the long comment hehe, this was a super interesting read)