Many moons ago, while I was getting my first real taste of women's cricket, my dad said something that got stuck in my memory: Female batters tend to play only classical shots. Before you rush to cancel my old man, you might want to know that he is a 50-year-old geezer who is active neither on X nor Substack. But, as young kids watching sport for the first time, we tend to select arbitrary reference points to understand the sport from, and the female bent to pick sweeps over slogs became one of mine. In this article I will make the case for the counterproposition: female cricketers in recent years have activated their funk.

First things first — my dad was broadly correct. Using a generous definition of unorthodoxy, I estimated that only 2.8% of all balls faced in women's T20Is between 2016 and 2020 saw an unorthodox shot being played; the corresponding figure in men's T20Is was 7.4%. But how times change. Since February 2023, the month of the first WPL season, this number has shot up to 8.1%. Consider the following statistic: the scoop shot, which during 2016-20 brought the batting side fewer runs than did the leave, is now being played twelve times as often. What used to be a classy ballroom dance has been turned into a rave party.

Central to this transformation is the opening up of a new area behind the wicket. Due to lower speeds of bowling in women's cricket, the area behind the wicketkeeper has historically been one of the game’s quieter zones. But there are also several reasons why this shouldn’t be the case - the absence of one extra fielder outside the ring, the smaller inner circle, and the slower pace of infielders being some - as long as one can summon the might required to send the ball shooting through this space. Arguably the greatest female batter of all time - Meg Lanning - has weaponized this by achieving timing so pristine on her late cut that it became her most productive stroke.

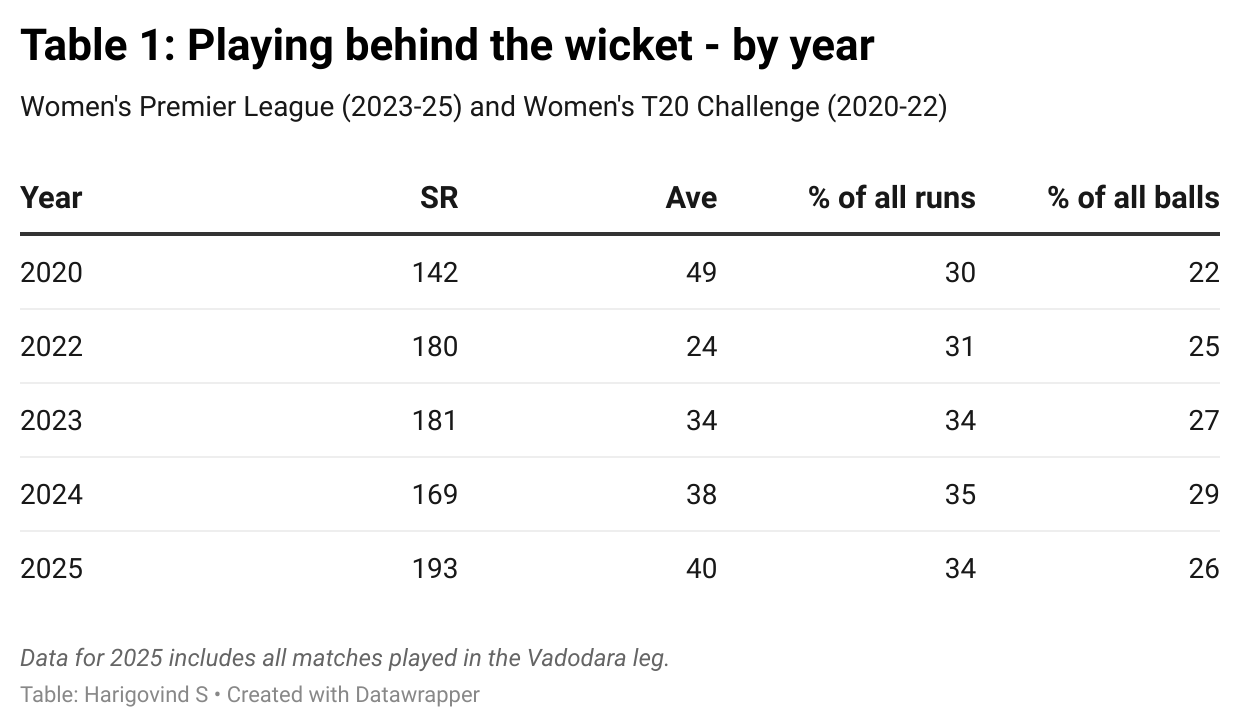

Only now the rest of the circuit is catching up. The above table compares the frequency and efficiency of shots behind square on both sides of the pitch, across five editions of leading T20 leagues in India - the WPL and its precursor, the Women's T20 Challenge. Not only are female cricketers playing behind the stumps more often, they’re also better at doing it. Yes, some of this is probably down to the good batting strips that have been rolled out in this time, especially in Mumbai and Bengaluru, but that doesn't explain the underlying shift in shot options. This suggests something going on at the deeper level of intent, rather than at the level of conditions.

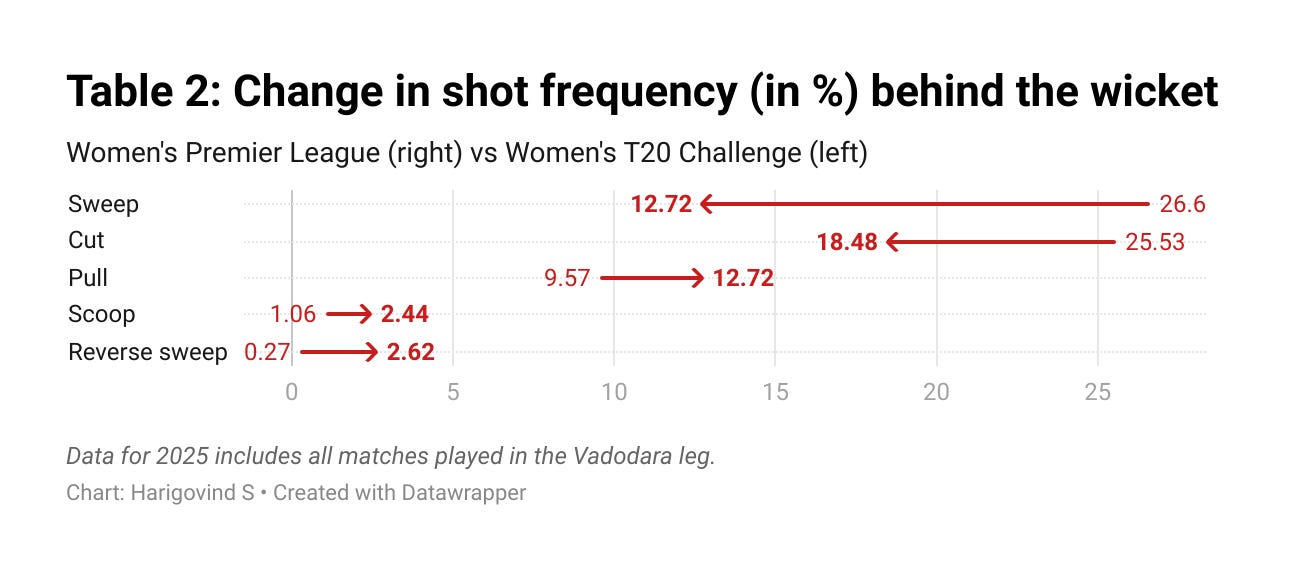

Table 2 fleshes out this distinction more carefully. In the Women's T20 Challenge era, as spinners bowled in the late 60s and early 70s kph, batters encountered the need to manufacture pace off the deck, so the traditional sweep shot ruled the roost. But in the WPL era, the proportion of sweeps has halved, allowing funkier alternatives to take its place — primarily the scoop but also the pull and reverse sweep. Batters once saw themselves as having few options other than get down on one knee to fetch the ball from outside off, they have now evolved to using smarter options against faster and more accurate bowlers.1

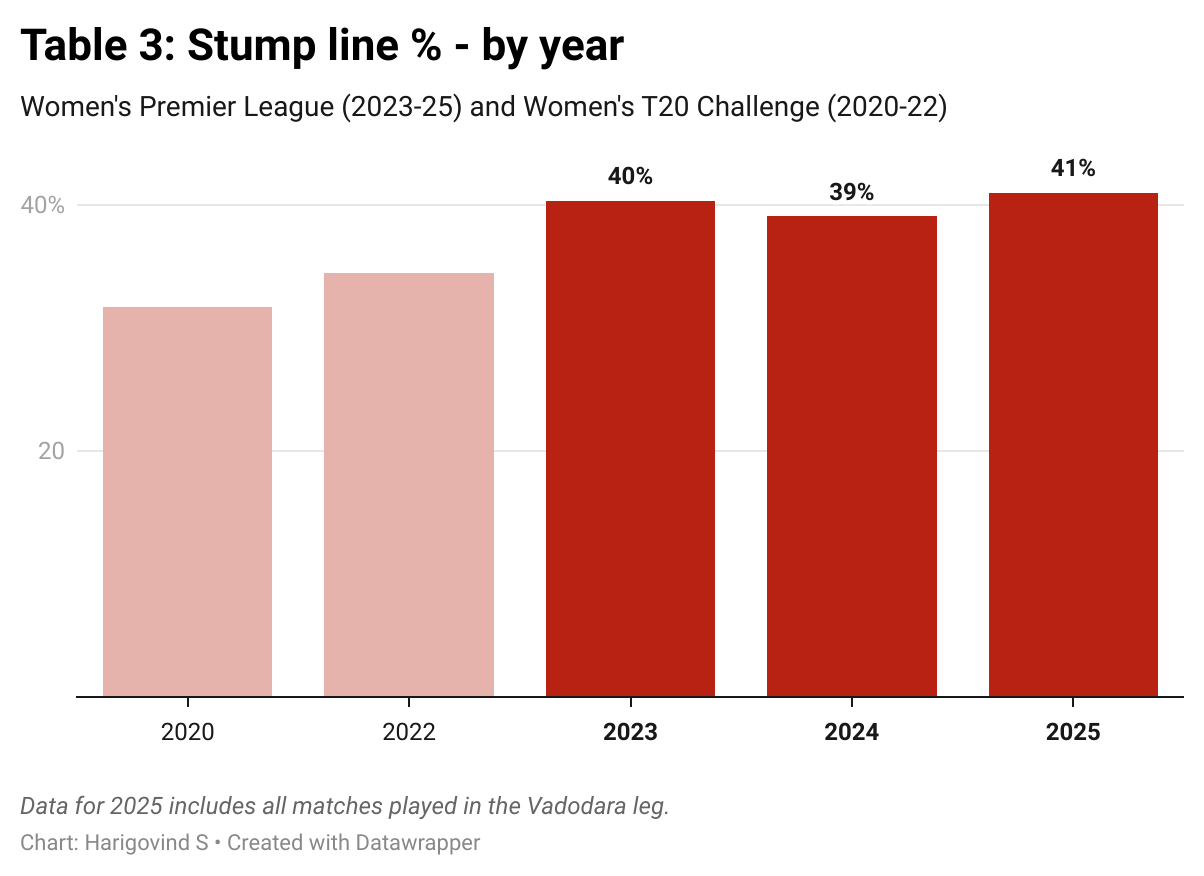

That’s right, fast and accurate bowlers. Arguably the most dramatic effect of the WPL on Indian cricket has not been on hitting intent or technique, but on bowling accuracy. Table 3 is based on manually tagged data - so take it with the appropriate amount of salt - but it illustrates a point that is obvious to those who have paid attention to women's cricket over the past five years: the proportion of balls hitting the stumps has been rising at a marvelous rate. I used to assume some years ago that the preponderance of the wide line in the women's game was a response to the importance of the sweep shot; now I believe it was merely a reflection of the inaccuracy that beleaguered the bottom half of female spinners in this age. But it is a pall that is slowly lifting.2

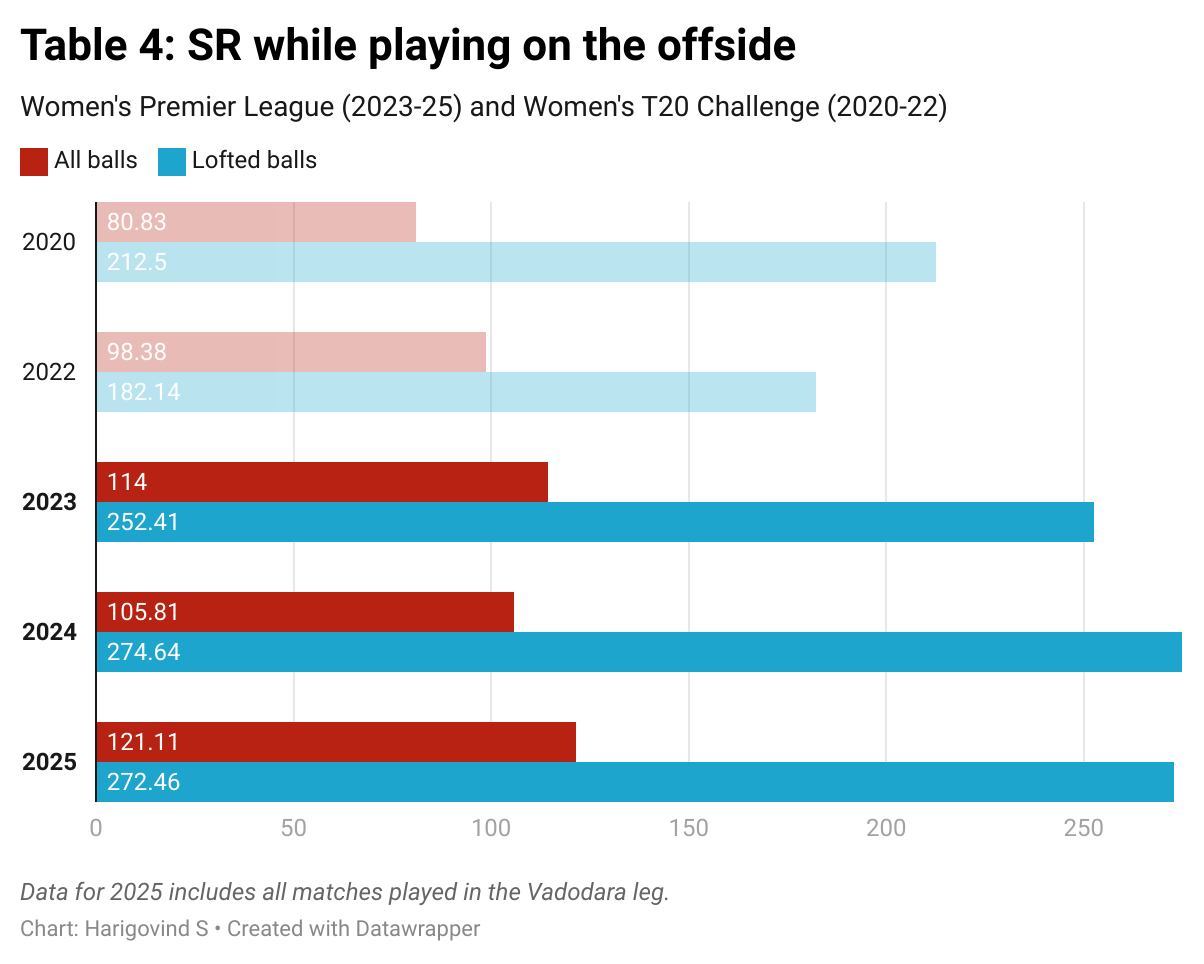

It is this rising bowling standard that makes the newfound funk in batters all the more remarkable. I've long been of the opinion that the litmus test for power-hitters is if they can drill the ball through the offside, because when hitting through this area one must generate all their power from their arms, as the hips cannot rotate. As we've seen, bowlers have corrected their lines in recent editions of the WPL. Yet, as Table 4 shows, batters have been targeting the offside boundary in front of square just as fervishly. The proportion of shots they play through this part of the field has fluctuated but the efficiency has risen, especially while lofting.

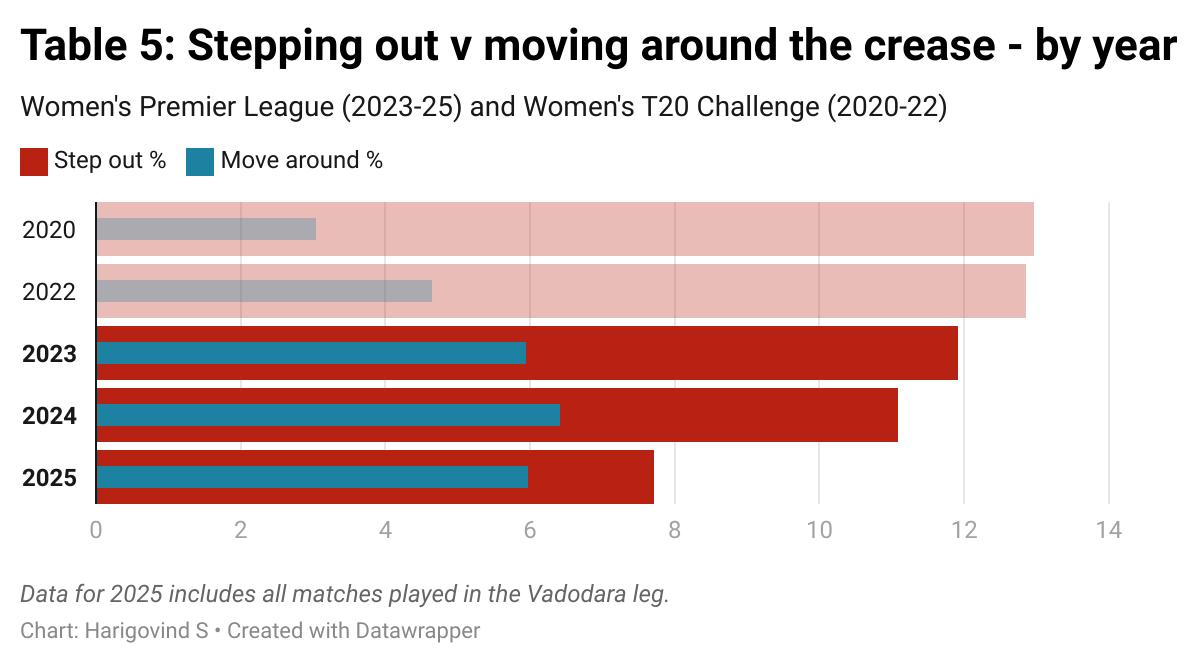

How is it possible that despite facing straighter lines batters are hitting to off just as ruthlessly? Because as bowlers have started pitching it on a straighter line, batters have begun moving around the crease more. Table 5 gives the proportion of all balls before facing which female batters have moved around the crease, or run down the pitch. Whereas five years ago, the main template for creating the room hitters need to flash their arms was to come down the pitch, today it is to step to the legside. For context, IPL batters in the league's most high-scoring season ever moved around the pitch against 5.99% of all deliveries. They were one-upped by the ladies last year, who were playing on trickier pitches and without the cushion of the Impact Player.

Need I spell out just how extraordinary all this is? It took a decade of analysts screaming at star cricketers for the men's T20 establishment to get where it is today. In just a matter of three years, with little formal year-round coaching and even less analytical interest, the women of the WPL have achieved levels comparable on several underlying metrics to top male hitters. They aren't nearly as efficient, but who can tell in the light of the last three years' evidence that ten years down the lane they won't be?

Much of this article wears a veneer of objectivity. Let me leave you with a thought that is sure to rile up at least some readers. Male athletes are motivated to take up sport for traditionally masculine reasons, be it patriotism or the pursuit of respect and glory. But female athletes aren't attracted to sport because it is a feminine pursuit. For this reason, I suspect that women's sport draws towards itself a base that rejects traditional gender norms. In other words, female athletes tend to be social and political progressives. They cut their hair short and paint it blue. You know what else political progressives are? They are open to new experience.

While it takes hours upon hours of intellectual sparring to convince Virat Kohli that it might be a sound idea to slog sweep in the IPL, Ellyse Perry buys into this suggestion wholeheartedly. Perhaps the openness of female athletes is why they have been scooping more and sweeping less; it is why they have been moving around the crease more; why they have been taking on the offside boundary with minimal caution; why they seem a lot more willing to risk being run out off the last ball of an innings for a miniscule collective reward. My pop was right eight years ago when he said to me that female cricketers play only classical strokes. He isn't anymore.

As I hint at in this paragraph, I firmly believe that the other way in which women’s spin bowling has changed over the past five years has been through the rising number of slow bowlers who operate in the late 70s and 80s kph. But I don’t have the data to confirm this, so that’s a story for another day.

Table 3 plots the percentage of deliveries tagged as having pitched in line with the stumps, not the more familiar metric that is the percentage of balls estimated to hit the stumps. So don’t compare these tall figures with those that you may remember seeing on TV.

This is fantastic Hari! Just wondering where you got some of the data from?

What an Amazing piece To Read, And Clear detailing about the Metrics